![Desiderio_del_cuоre]()

Michael

Mikaël

|

Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer

1924, Denmark — 86 minutes, black & white, aspect ratio 1.33:1 — Drama

The first great film from legendary writer/director Dreyer, and a powerful landmark in the history of Gay Cinema. |

Review

![Image]()

With Michael (1924), cinematic genius Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889–1968) created not only his first great and fully-realized film but, with its nuanced and sympathetic understanding, a landmark in the history of Gay Cinema. This tale of a gay/bisexual/straight love triangle becomes, in Dreyer’s hands, a powerful work of both immense visual beauty (shot by legendary cinematographers Karl Freund and Rudolph Maté) and deep psychological insight. At once stylistically innovative and emotionally engrossing, Michael belongs in the company of Dreyer’s five later, better-known masterpieces: The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928; the single greatest film I have seen), Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964). The DVD from Kino is first-rate, featuring a restored print, an evocative original piano score, and an optional commentary track by a scholar of Danish cinema.

Michael dissects the complex relationship between a celebrated, discreetly-gay painter named Claude Zoret (Benjamin Christensen, director of Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages), the shrewd but penniless Countess Zamikoff (Nora Gregor, Rules of the Game), and the handsome title character whom they both desire (Walter Slezak, Hitchcock’s Lifeboat). Against this emotionally charged background, Dreyer creates one of the great films about what it means to be an artist – as well as what it means to love, whatever your sexual orientation. Dreyer counterpoints the main action with a purposefully melodramatic subplot about an affair between the beautiful young Alice Adelsskjold (Grete Mosheim) and the dashing Duc de Monthieu (Dider Aslan), and what her middle-aged husband (Alexander Murski) does about it. As Michael, whom Zoret has adopted as both protégé and son, plunges from the delirious heights of new love with Zamikoff to the depths of theft and guilt, and as Alice and Monthieu’s adultery spirals out of control, Zoret experiences a revelation about his work and life.

The facts of Dreyer’s life are widely available, so his biography can be briefly summarized: he was born illegitimate in 1889, grew up in foster homes, proved a gifted student, excelled as a journalist, in 1912 wrote his first screenplay (ultimately sold two dozen) while simultaneously working as a film editor, in 1918 directed his first feature, The President, and with three more pictures solidified his reputation as a brilliantly promising filmmaker, then caught the attention of the world-renowned German studio, UFA.

Dreyer based Michael on the gay Danish author, and theatre director, Herman Bang’s classic “decadent” 1902 novel of the same title (here is a free, unabridged online edition of Bang’s original novel Mikaël in Danish – no English translation is available). Since the film was produced by the great Erich Pommer (who also shepherded The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, and The Blue Angel) of UFA, Dreyer was forced to share the screenplay credit with the studio’s powerful head writer, Thea von Harbou, although the script is solely by Dreyer. (Von Harbou is famous for writing such seminal works by her then-husband Fritz Lang as Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Metropolis, and M, even as she is infamous for staying in Germany to work for the Nazis, while he fled to Hollywood.) ![*]() To see Michael in a historical context, here are brief remarks on Germany in the 1920s: History, Cinema & GLBT Life, from my review of Different From the Others.

To see Michael in a historical context, here are brief remarks on Germany in the 1920s: History, Cinema & GLBT Life, from my review of Different From the Others.

![Image]()

Dreyer went to enormous lengths to ensure that every item on display was authentic, from costumes to art objects. The paintings, statues, furniture and jewelry are not mere props, but works of fine art, personally selected by Dreyer and his inspired production designer, Hugo Häring. (Häring, who worked on only this one film, was an influential architect and theorist, specializing in surprisingly beautiful and humane buildings for livestock: an admiring 2001 Guardian article on him was entitled “From Bauhaus to Cow House” – here is a 2.5MB PDF download of the fully-illustrated monograph Hugo Häring and the Secret of Form from the Royal Institute of British Architects). Michael‘s publicists had a field day, writing about the special security guards, on duty 24/7, protecting the costly treasures. Zoret’s studio was modeled closely on the actual studio of Auguste Rodin, who also served as the inspiration for Bang’s Zoret. Dreyer was adamant about the complete authenticity of the world of his film, down to the smallest detail, and producer Erich Pommer, who enormously admired Dreyer’s earlier pictures – such as the Griffith-like epic Leaves From Satan’s Book (1919), the comedy The Parson’s Widow (1920), the drama Love One Another (1922) about the persecution of Jews in pre-Revolutionary Russia, and the fairy tale Once Upon a Time (1922) – gave him everything he wanted on Michael.

![Image]()

UFA and Pommer hoped that by making this a lavish, big-budget production, they could definitively break into the lucrative American market. But despite rapturous reviews from all of the German critics, the film never found a distributor in France and several other international markets. When it was finally released in the US in 1926, it was packaged as a homophobic ‘freak show’ under two new titles, either The Inverts or Chained: The Story of the Third Sex, with an uplifting “scientific lecture” tacked on and Dreyer’s name removed. Although none of the reviewers dared mention homosexuality, they were still brave enough to subject it to universal, sneering condemnation: The New York Times then referred to it as “junk.”

Now, of course, both that august newspaper and audiences around the world realize that Michael is, if anything, the antithesis of “junk.” With our understanding of Dreyer’s genius, as well as our increased comfort levels with gay-themed cinema, we can appreciate the film on its own terms.

Few filmmakers have ever been so adroit at inspiring such deep and true performances, not only in his universally-admired later films, but here also. Dreyer allows each member of Michael‘s extraordinary cast, from the leads to the smallest bit players, to express their character fully, even as he blends their performances with his larger aesthetic goal of combining the elaborately theatrical with the poignantly restrained. Michael most resembles two other Dreyer films, The Passion of Joan of Arc and especially Gertrud, in its focus on externalizing the main character’s nature (here, despite the title, it is Zoret) through every available cinematic means, from performance and setting to lighting, composition and editing. Few films, from any period, have such an enormous range of psychological detail, whether we are experiencing the emotions of an aging master painter whose powers are (temporarily) blocked and who is losing the protégé/adopted son he loves and who inspires him, or the enormously tangled feelings of that young man torn between his loyalty to the artist and his desire for the seductive countess: we are allowed to feel every step of Michael’s descent into deceit and theft. Yet for all Dreyer’s emphasis on exploring nuances – often through close-ups, in which every minute movement of the character’s skin and eyes is revealing – his greatest films, as here, are never less than emotionally riveting.

![Image]()

To bring his vision to the screen, Dreyer collaborated with two of the world’s greatest cinematographers: Karl Freund (also shot The Last Laugh, Metropolis, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, Browning’s Dracula; and director of the 1932 The Mummy), who shot all of the interior scenes, which comprise most of the film, and Rudolph Maté (also photographed The Passion of Joan of Arc, Vampyr, To Be Or Not To Be, Gilda; and director of the 1950 Noir classic D.O.A.), who did the few exterior scenes and, some believe, the ballet sequence. Trivia buffs take note: Freund’s only on-screen performance is in this film, as the jovial, rotund art dealer, Leblanc. The seamless, not to mention inspired, look of the film, despite the presence of two distinctive directors of photography, is a credit to Dreyer’s mastery. Michael offers the first complete realization of his visually extravagant yet emotionally precise style.

It should be noted that Dreyer was also a genuinely insightful, and modest, commentator on his own works. Although the indispensable collection of his writings, Dreyer in Double Reflection: Translation of Carl Th. Dreyer’s Writings ABOUT THE FILM (OM FILMEN), edited with commentary by Donald Skoller (1973), is out of print, Dreyer’s single most important essay is available online, unabridged and free: “A Little on Film Style” (1943), although the Criterion Collection has mystifyingly retitled it “Thoughts on My Métier.” If you are interested in hearing Dreyer talk briefly about all aspects of his work – image, rhythm, drama, acting, makeup, diction, and music – you will likely enjoy this unique piece. (Criterion has released gorgeous, definitive DVD editions of The Passion of Joan of Arc, plus a box set of Day of Wrath, Ordet, Gertrud, and Torben Skjødt Jensen’s excellent 1995 biographical documentary, Carl Th. Dreyer: My Métier; you can complete a collection of Dreyer’s six masterpieces with Image Entertainment’s DVD of Vampyr, although the picture and sound quality are muddy [I saw a pristine print of Vampyr at New York City's Film Forum a few years ago], and, of course, this excellent Kino DVD of Michael.)

Let me add that I was once fortunate enough to have seen all of Dreyer’s existing works at a series in Los Angeles; and I have watched his major films many times – always finding new elements to admire and enjoy. But at that complete retrospective, by far the greatest revelation was Michael; I was unprepared for the sheer beauty and power of this long-neglected but great early work.

Briefly, what I like so much about Dreyer is that we can respond to his films deeply on a purely intuitive level (as on a first viewing), but then the more closely we look at his greatest works – exploring layer within layer of stylistic beauty, psychological insight, and even (if you are so inclined) spiritual wisdom – the more we can appreciate the unparalleled fullness of his vision.

![Image]()

We can savor how he connects each element to every other one – characters, decor, lighting, meticulous compositions, movement and stillness – playing them off each other, to create a fully-realized work which is even greater than the sum of its sensuous parts. Beginning with Michael, Dreyer’s six masterpieces come as close as any films, or novels or plays, which I know to approximating the complexity and beauty of lived experience. (If I may be allowed a brief literary excursion, the closest analogy to what Dreyer achieves in film is perhaps the subtle and densely beautiful novels of Henry James (1843–1916), including The Portrait of a Lady, The Wings of the Dove, and The Golden Bowl. Although not even the best-intentioned film adaptations have fully succeeded at capturing the essence of James, astonishingly Dreyer here creates an ideal cinematic analogue to his intricately nuanced fiction. Had James, who was gay, lived eight more years, it would be fascinating to hear his thoughts on this film, which in the character of Zoret coincidentally parallels aspects of his own life.)

Perhaps a good way to first experience a Dreyer film is just to let it flow over you; don’t worry about ‘what it means’ or how it works, just let it engulf you. Then, if you connect with it, you might want to look at it more closely.

Now let’s explore how Dreyer uses narrative structure in Michael, deepens it with his innovative use of visual style, and finally unifies the entire film through Zoret. NOTE: PLOT “SPOILERS” AHEAD! I have structured this review so that, until now, I could discuss many aspects of the film without revealing the narrative’s major twists and turns. If you have not yet seen it, and do not want to know about those developments, read no further. Otherwise, here we go…

Dreyer was always proud that with Michael he either invented, as some historians claim, or at least defined, an important film genre: the Kammerspiel (literally “chamber play”). Although this was an outgrowth of a theatrical movement begun by stage director Max Reinhardt and playwright August Strindberg (The Dance of Death), Dreyer reconceived it for the screen. Kammerspiel films, like Michael and Dreyer’s Master of the House (1925), are characterized by their concentration on a few characters, minutely exploring a crisis in their lives during a brief time period, and using slow, evocative acting and telling psychological details. The next major example of Kammerspiel was Murnau’s profoundly moving The Last Laugh (1924), shot by Karl Freund right after this film. (Ironically, these first great “chamber play” films were not based on theatrical works: Dreyer used a novel, and Murnau an original scenario.)

The most conventional element in Michael is the classical narrative structure. It follows the traditional arc of rising action (Zoret’s painting has brought him wealth and fame, thus attracting not only the comely youth Michael but, as the film begins – “inciting incident” time – the gold-digging yet ethereal Countess Zamikoff), climax (Michael is leaving Zoret for Zamikoff, with whom he is infatuated; Zoret is blocked as an artist; also the parallel subplot of young Alice Adelsskjold cheating on her middle-aged husband with a dashing duke), and resolution (Zoret achieves his greatest fame at a new exhibition; Michael sinks lower into deceit and theft, finally bottoming out as Zamikoff’s boy-toy; Zoret has an epiphany about his work, life and the meaning of love – then promptly dies). The plot moves ahead in linear fashion, with only a couple of exceptions. There is one flashback near the beginning, in which we see the crucial scene of Zoret and young Michael’s first meeting, and a later ambiguous, almost dreamlike scene of Michael and Zamikoff strolling through a meadow (which looks ahead twenty years to a comparable scene in Days of Wrath – unless it’s purely a fantasy of Zoret’s, in which case it anticipates the hallucinatory Vampyr.) Dreyer also sets up, from the first scene, a subplot between the age-dissonant Adelsskjolds and the Duc de Monthieu, but he does not often bring them onscreen (later I will look at how Dreyer uses this subplot for added thematic density).

![Image]()

As Casper Tybjerg notes on the commentary track, Dreyer’s screenplay very closely follows Bang’s novel, which is already written in what he describes as a cinematic, albeit impressionistic, style. Although Bang was, at the time, one of the most highly-regarded modern European writers, Dreyer and others found this particular book rather “tinsely… and superficial.” Dreyer did, however, praise its “genuine tragedy [and] concentrated atmosphere.” Some people may go trolling for instances in Michael of the classical myth of Jupiter, king of the gods, who falls in love with the beautiful youth Ganymede and whisks him off to Mount Olympus as one of his many, both male and female, lovers: note the plot point about Michael, the Ganymede stand-in, and the English glasses (Ganymede’s title was “cup-bearer” to the gods). But that use of myth seems like a minor holdover from the novel, rather than a source of added richness to the film. (Apparently the Jupiter/Ganymede myth is more prominently used in the great, and gay, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller’s version of Bang’s novel, re-titled Wings (1916), which is reportedly freer both in its use of the storyline and in overt homoeroticism: Zoret, who is there a sculptor, has scenes with an almost-nude Michael posing for him; Dreyer claims never to have seen this version, although he was a great admirer of Stiller.)

More interesting than the film’s overt structure is how the narrative suggests a predetermined, fatalistic worldview. Every major character, plot and subplot development is introduced in the long opening scene, from the double motif of infidelities (Michael’s and Alice’s) to a small detail like the introduction of Zoret’s Algerian sketches, which at the end of the film allow him to paint his masterpiece. What we see at the beginning, even if only hinted at, we will see resolved, in one way or another, by the final reel. Dreyer keeps the world of his film closed both dramatically and visually and, with one important exception, psychologically and spiritually too.

![Image]()

Like so much of what is great in this film, the plot and characters are simultaneously clear yet ambiguous. We think we know these people – we certainly know what they are doing – yet we can’t help feeling that they have depths, and depths within depths, which we can only sense. Dreyer uses his astonishing mastery of image not only to plumb their souls, but to wrest from them larger implications which each of us can ponder in our own way.

From the very first shot, Dreyer shows us the paradoxical space in which Zoret lives, and in which this “chamber drama” takes place. With deep focus, we see the multiple planes of action of a vast, almost cavernous, vaulted room, filled with the most eclectic art works (from classical to Gothic to modern). We instantly feel exhilarated by the sheer scale of the room, and the sheer variety of its decorations – yet it’s also constricting, like an enormous, airless cage. As the film progresses and we see yet more of Zoret’s mansion, we realize that it is a singularly apt metaphor for Zoret’s life, as well as perhaps his and Michael’s – and even Michael’s and Zamikoff’s – relationship. Already, Dreyer is using design to make connections between the inner life of his main character, Zoret, and his environment.

![Image]()

As striking is the other principal location, Michael’s apartment (which we first see about halfway through the film, when he takes Zamikoff their for their initial tryst). The life of the tortured Michael – pulled between his feelings for his teacher, adoptive father and possibly lover Zoret, and his white-hot passion for Zamikoff – is reflected in the two levels of his lavish duplex, which are joined together by a tortuous spiral staircase. Upstairs is art (although we never see Michael, the would-be artist, paint except when he does the eyes on Zoret’s portrait of Zamikoff) and downstairs is conspicuous consumption (including his collection of then-current movie dolls: Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Lon Chaney are instantly recognizable). Of course, Zoret pays for everything that Michael has. It’s also worth noting that in Zoret’s house art is everywhere, from floor to ceiling; while in Michael’s bachelor pad, the art is confined to his studio, completely cut off from where he does his living.

Michael’s visual changes throughout the film subtly indicate his devolving psychological, and moral, state. We first see him posing like a narcissistic young model, later we see him as a boy (both in literal form in the flashback, as a teenager, and in metaphorical form as someone to be patted childishly on the head, first by Zoret and later by Zamikoff), then as a young artist painting the countess’s eyes (this is the only time he wears an “artist’s” scarf), then as a young ballet-going cosmopolitan lover, as a suppliant at Zoret’s feet, and finally as a dressed-up toy for Zamikoff to play with when she’s not cradling him in her arms. For that final image, the performances and compositions make it clear that their relationship is more constricting, and pathetic, than nurturing.

![Image]()

Dreyer also uses a range of objects, both for their inherent beauty and for what they reveal about the people associated with them. For instance, note how Zamikoff is frequently shown with different kinds of fans. Like them she stirs things up, even as we and Zoret, although not Michael, can see through her. In yet another instance of elements tying together in multiple ways, note that Dreyer has made (gay icon) Tckaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake what Michael and Zamikoff see in the theatre (in a sequence which is perhaps the best capturing of live theatre on film that I know), and not as in Bang’s novel a contemporary play. Swans and feathers just go together; but also the ballet’s plot, about romance, deception, delusion, and finally “triumphant death,” adds yet another parallel to the film’s love triangle (even as it foreshadows Zoret’s final epiphany cum death). In a playful – yet slightly sinister – mood, Dreyer shows that Zamikoff has definitively hooked Michael by framing him “trapped” behind her feathery hat.

That shot also reminds us that Dreyer is, even this early in his career, a master of composition. The sheer beauty, and character/psychological and thematic implications, of his images is nearly limitless. The works of very few filmmakers can withstand the scrutiny which Dreyer invites. Although in this review I can only look at a few of his extraordinarily rich visuals, if Dreyer’s films spark your curiosity, know that you could be in for a lifetime of happy scrutinizing: skoal!

The most astonishing visual element in this film, and perhaps Dreyer’s greatest contribution to the language of cinema, is his revolutionary use of the close-up. Although Michael‘s close shots are not as shattering as those in The Passion of Joan of Arc, four years later, they are nonetheless powerful, beautiful and exactly what this film needs.

![Image]()

The eyes may be the window of the soul, but Dreyer prefers a slightly larger scope: the entire human face, with all of the thought and feeling which sometimes even the smallest muscular movement can reveal. In Dreyer at his best, the actor’s face can be as moving, even electrifying, as any full stage performance.

In 1939, Dreyer revealed how on Michael he first learned to combine drama, visual style, and psychology through a pioneering new use of close shots (the following is transcribed from Casper Tybjerg’s DVD commentary track):

Nothing in this film is important apart from the psychological conflicts whose dramatic development can only be reflected in subtle facial impressions that could only be reproduced in close-ups…. I learned to strive to get each individual performance to be genuine, to be felt. I discovered that there was a very particular difference in nuance between the performance that had been fashioned under the control of the intellect and the felt performance where the actor had been able to eliminate all other feelings than just that one the emotional makeup demanded by the performance. And I realized that the director had a very clear and significant task consisting in adjusting the actor from the outside and leading towards the goal which, in the large close-ups, must be to forget himself, to shut off the intellect and open up the heart.

To achieve this, Dreyer as director used a restrained manner, speaking “quietly and consistently with each individual actor.” He created a safe space in which they could open up and express, both emotionally and physically, the fullness of their character. The results were a landmark in both film acting and visual style: subdued but intense performances, matched by evocative close-ups; and, as we will see, the combined effect is even greater than its constituent parts.

With this innovative technique, Dreyer consciously moved away from the stagey tableau style of cinema’s first quarter century, although he admitted that he conceived his approach by studying Griffith’s close-ups of Mae Marsh’s character in Intolerance. Before Michael, a close-up was merely an insert, always filmed along the same axis as the master shot and staged solely to highlight a plot-related element: like a theatre-goer using opera glasses to highlight a particular detail. No filmmaker before Dreyer had consciously used such telling close-ups, and editing, to reveal the psychology of a character’s gaze.

![Image]()

To take just one example, look at the superficially quiet but emotionally-fraught dinner scene, in which Zoret and Zamikoff subtly vie with each other for Michael – their body language is as eloquent as any dialogue could be – while the pretty lad sits there feeling ignored, oblivious to the fact that he is the sole object of their attention. Dreyer purposely downplays Zoret and Zamikoff, showing them only in carefully-balanced long and medium shots, since he has earlier established their competition for Michael. Instead, Dreyer gives us close-ups only of the title character, whose slouching posture, pouting lips and downcast eyes reveal his selfishness, and self-blindness. This scene also indicates how Dreyer inflects a scene, not necessarily with the most obvious drama (Zoret and Zamikoff’s subtextual “battle”) but with what is most truly revealing about the characters and themes.

In addition to using close-ups to heighten emotional intensity, Dreyer has also increased our direct involvement. The technique compells us to fill in not only the implied story points but, more indirectly, our impression of the overall character. We must extrapolate their entire nature, at a given time, with only their malleable face as clue.

Although his close-ups may superficially resemble those in early cinema, they could hardly be more original, both psychologically and aesthetically. Speaking of Dreyer’s relation to early film, it’s interesting to speculate that he cast the great Danish director Benjamin Christensen in the lead role of Zoret for more reasons than his obvious brilliance and depth. On one level, Dreyer revered him – as many still do today – as the first great Danish filmmaker (his unclassifiable 1922 film Häxan, also called Witchcraft Through the Ages – part documentary, part melodrama, part hallucinatory trip – is one of the most jaw-dropping pictures I have ever seen). Theirs was hardly a Zoret/Michael relationship, but still Dreyer saw Christensen as a sort of artistic father figure, an “old master,” although their ages were only 10 years apart. Christensen already represented the past, as part of the first great but already-fading generation of directors – including Louis Feuillade (Fantômas, 1913), Giovanni Pastrone (Cabiria, 1914), and D.W. Griffith (Intolerance, 1916) – whom Dreyer, and the other ambitious young turks in cinema’s second generation, felt the need to supplant. In this film, there is no indication that Michael will ever fill Zoret’s shoes, but behind the camera, Dreyer went far beyond the achievements of even Christensen.

![Image]()

Let’s look at how Dreyer extends his patented close-up technique in Michael. Close-ups, whether evocatively nuanced or just literally in your face, have become utterly commonplace for decades; television was and is all but defined by them. So it is difficult for us today to realize just how radical Dreyer’s innovation was at the time. What does jolt us are two of Dreyer’s related devices, which are virtually never used today. First, he often augments his close-ups by using an iris, isolating the face within an oval-shaped space surrounded by blackness. There are dozens of instances throughout the film. In a couple of cases, such as when he wants to focus exclusively on Zamikoff’s eyes (which Zoret is having such difficulty painting), he literally masks off the bottom of the frame, hence multiplying the overall effect. Iris shots were then common – look at any Griffith film – but most often used as punctuation, to definitively end a scene; for an ironic modernist use of the iris, note how Welles employs the device in The Magnificent Ambersons, set during the “silent era.” But Dreyer uses the iris in a manner that is different from both Griffith and Welles. Dreyer uses it self-consciously but aesthetically and seriously too. The effect is beautiful and striking in its own right, but Dreyer also uses it to focus our attention on the character. Further, as we will see below, he gives the iris a commentative, even a moral, weight in defining the characters and his themes.

![Image]()

For us, an even more radical technique – which you might only expect to find in, say, Godard or Fassbinder at their most Brechtian – comes in the rare but striking scenes in which Dreyer uses an actual moving spotlight to accentuate psychological details, as in the pivotal ‘painting Zamikoff’s eyes’ scene (Zoret cannot connect with this rival for Michael’s love, hence cannot paint her eyes convincingly – but Michael can). The ‘moving spotlight’ allows Dreyer to preserve the spatial continuity in a single shot, while simultaneously shifting our focus from one major character to the other: they are at once united in the frame but divided by the unsettling shift in darkness to light, then light to darkness. In the scene just mentioned, Dreyer further intensifies the emotional effect through almost the only instance of camera movement in the entire film (despite the immense size and weight of the camera, he wanted more tracking shots, but Freund was saving those for Murnau in the film he would shoot next – the first great use of expressive camera movement in cinema – The Last Laugh).

Perhaps to prepare the audience, Dreyer first introduces the ‘moving spotlight’ device in a naturalistic form, in the crucial first scene between Zoret, Zamikoff and Michael, in which he holds a spotlight so that she can see The Master’s greatest painting. After a moment, she realizes that the beautiful, scantily-clad youth in “The Victor” is none other than Michael. You can sense the penniless countess instantly calculating both Michael’s lover potential and access to money, via Zoret, even as she deduces the nature of the men’s relationship.

An especially compelling example of the ‘moving spotlight’ technique occurs in a two-shot between Michael and Zamikoff at the ballet, as we see Michael in a bright light slowly fade into darkness, while the countess almost seems to suck the light away from him and shine it on herself. This imaginatively parallels the psychological and thematic point of Michael’s willing fall and her rise in power over him. From a larger perspective, the shot also crystalizes the entire ballet sequence – which is extraordinary for fully capturing the experience of live music theatre on silent film – even as Dreyer’s mastery of filmmaking is revealed in his brilliant juxtaposition of shots between the ballerinas on stage and the four young almost-lovers watching them, both Michael and Zamikoff and, from the subplot, Alice and Monthieu. Dreyer creates a flawless union of composition, light and shadow, movement both within frames and between shots, and drama, to express not only the psychology of his characters but the phenomenal potential of film.

Dreyer’s most poignant use of the iris-effect close-up comes in the final sequence, with Zoret on his deathbed, having at last come to self-understanding: “Now I can die in peace, for I have seen true love.” In a moment we’ll come back to the full, and perhaps surprising, implications of that (seemingly) morbid sentiment, but now let’s focus on Zoret, as both the complex “gay figure,” in what I believe is the first masterpiece of GLBT cinema, and the consciousness who determines much of the film’s visual style and thematic resonance. As we will see, Zoret is the key, both to the film and to its meaning, which includes its complex relationship to gay identity.

Some people wonder if Michael should even be classified as a “gay film,” since there is no overt display of same-sex relations – not even a quick kiss between Zoret and Michael (of course in Dreyer glances count for a lot, and there are plenty). Neither are there any pleas for understanding and tolerance of sexual diversity, as in Richard Oswald’s moving but polemical 1919 release Different From the Others, which centers on another artist/protégé pairing (although the German gay emancipation movement vigorously championed Michael, before being hauled off to concentration camps by the Nazis). Even the term “homosexual,” in any of its then-popular forms, is never once mentioned – except on the luridly-retitled, and disastrous, US release when Michael became “The Invert” or “The Third Sex.” So can this be seen as a “gay film”? My answer is a resounding yes, both because of the history found behind the scenes and for what we see on the screen.

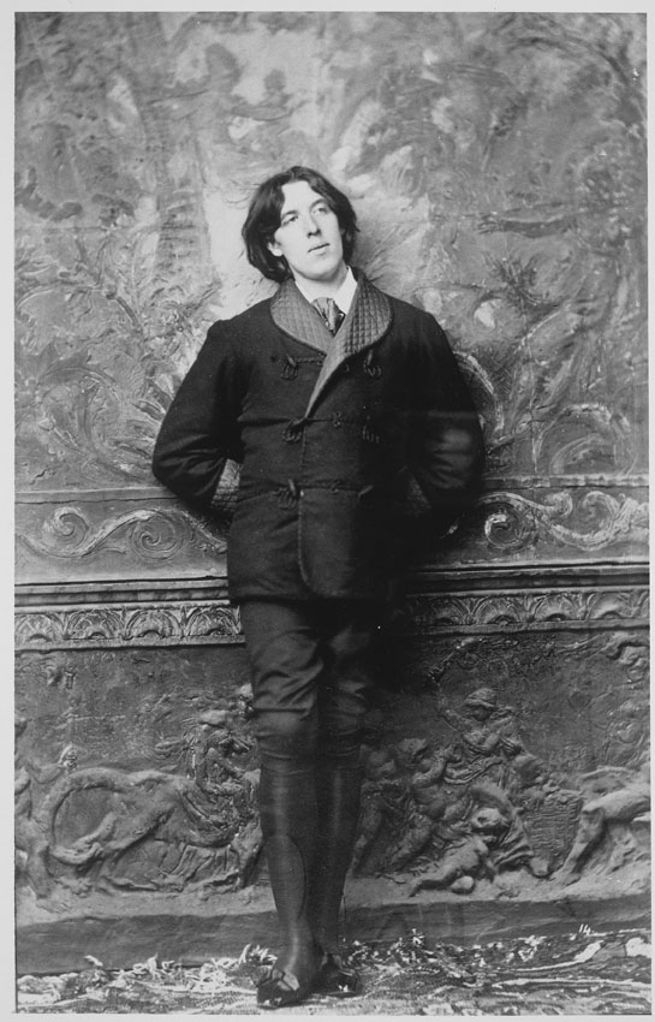

Same-sex history takes many off-screen forms with Michael. Most obvious is the acclaimed Danish novelist Herman Bang, whose novel Dreyer follows so faithfully. Bang was a well-known out gay man, a sort of Scandinavian Oscar Wilde. Although never arrested, he was intermittently harassed by police and the Danish tabloids. In late 1906, after a scandal erupted, the press declared that “an unclean puff like Bang must be beaten down… [He is] like poisonous gas.” At the same time, in cultural circles, Bang was regarded as one of the best novelists of his time, as well as one of Europe’s most important theatre directors, with over eighty productions to his credit. Among the German pro-gay movement, two decades before Dreyer’s film, Bang’s original 1902 novel was hailed as a milestone of gay literature (making it all the more frustrating that there is still no English translation). An early titan of Swedish cinema, Mauritz Stiller (Erotikon, 1920; Gösta Berling’s Saga, 1924), was also lauded for creating a landmark same-sex film, with his more openly homoerotic 1916 adaptation of Bang’s Michael, retitled Wings.

![Image]()

Dreyer himself was candid about exploring homosexuality in his film, saying that “I strove to make the film neither more nor less homosexual than Bang’s” novel, adding that gay people “do not run around with a big sign on them.” (Hmmm.) Recall the historical context, at the time of both Bang’s novel and Dreyer’s film. Gay men were still subject to imprisonment in most countries; Germany, where Dreyer made his film, had the draconian Penal Code Paragraph 175 – although it was rarely enforced during the brief “free speech” period of the 1920s, before the Nazis seized control. Although I have not seen Dreyer identified as bisexual or gay, as a well-educated cosmopolitan, with gay friends, he likely knew about the “secret tradition” of the many gay, lesbian and bisexual contributors to, even creators of, Western culture in literature, art, music (including Tckaikovsky), even cinema (including Stiller, Murnau, Eisenstein). Bang even reached back to antiquity, suffusing his plot with elements from the story of Jupiter and Ganymede. (Throughout the Medieval centuries that myth served as a code for gay men to identify each other; it was supplanted in the Renaissance by the hunky but well-bound figure of St. Sebastian.) Bang evocatively summed up his own, and likely countless others’, feelings about his status – at a time when he could have been hauled off to prison simply for expressing his own true nature – when he said that being gay “is like staying in a hotel and never knowing if you can pay the bill.”

![Image]()

In Dreyer’s film, there is more same-sex activity on screen than at first meets the eye. I’m sure that many viewers have asked about Zoret and Michael, Do they or don’t they? Is Michael straight, and merely doing ‘gay for pay’ – or simply living off of Zoret? Or is Michael bisexual, since at times he seems to care more passionately about the painter than you would expect from even a protégé cum adopted son? Neither Bang nor Dreyer are telling.

Although Dreyer does not include any scenes of Michael posing in the (almost) buff, as Stiller does in Wings, he seems remarkably comfortable in photographing the young man to highlight his conspicuous beauty (how differently Slezak appears, twenty years later, as the garrulous Nazi commander in Hitchock’s Lifeboat, or co-starring as Panisse in the 1954 Broadway musical of Pagnol’s Fanny.) Making women, especially young ones, shine has been at the (voyeuristic) heart of film since day one; but until the recent Male Underwear Model Era it was extremely rare for any filmmaker to make men look beautiful: ruggedly handsome, yes; sensuous, no. In countless films women were photographed with a soft diffusion filter and the most glamorizing possible light (even if they are portraying a working girl), while the men are shot straight on.

![Image]()

In one major instance, Dreyer ups the ‘gay quotient’ of Bang’s novel, when he makes a rare character change. In the book, Zoret’s devoted chronicler, Switt, is an inveterate womanizer, while in the film he has eyes only for The Master. Actor Robert Garrison brings the irascible, cigar-chomping Switt to life. His final scenes with Zoret – Switt stays at his side, while Michael is off cavorting with the countess – are among the most moving in the film. Although we only see glimmers of the love between Michael and Zoret, there is no mistaking what Switt feels for the artist.

At the end of the film, when Switt stands on the street and calls up to Michael’s apartment, there is almost a transference between Zoret’s perspective and Switt’s. He sees her, not as the alluring woman of Michael’s gaze, but as a shadowy figure, imprisoned – and re Michael, imprisoning – behind shadowy bars.

![Image]()

Structurally, Dreyer uses the brief subplot – of Monthieu, Alice and her husband – to counterpoint the main love triangle. Radical for its time, Dreyer highlights the equivalency of opposite-sex and same-sex “forbidden love” relationships through the many similarities of the two triangles. Both have young lovers choosing others of their age instead of their aristocratic older partners; both illicit couples are first aroused via works of art (the paintings of Michael and of Zamikoff in the main plot; the small classical nude in the subplot – tellingly, the small statue has literally lost her head); both affairs begin in earnest at the performance of Swan Lake (note how Dreyer places the young lovers in a theatre setting to expose the connections between passion and artifice, as he moves us, sometimes dizzyingly, between the characters in their boxes and the “doomed love” fantasy being danced onstage). Ultimately, Dreyer shows us that Michael’s infidelity to Zoret is the “moral equivalent” (to borrow a phrase now in vogue) of Alice’s betrayal of her husband. While both older men have been comparably cuckolded, one young male (Monthieu) is dead (ironically, he expires at the foot of a huge, toppled stone cross), while the other has sunk lower than you might have thought possible. The benighted title character has gone from a pretty-boy painter manqué to a liar and thief, now no more than a plaything for the countess – and of course once the money he inherits from Zoret runs out, so will she.

Now let’s look at how the film’s narrative structure, visual strategy, even its themes and larger implications, all revolve around Zoret.

Although Zoret may be defined by his unrequited love for Michael, through a richly nuanced performance, Dreyer and Christensen make The Master the most psychologically complex gay character we will see for decades (albeit without ever mentioning the orientational “h” or “g” words). Of course, Zoret, like any individual, is much more than just his sexual identity. What makes this wealthy middle-aged artist a character which we can identify with, despite possibly different career paths and financial situations? Superficially, Dreyer also made a major change in Claude Zoret’s appearance from the novel. There he is modeled on Claude Monet – the similarities of names was intentional – complete with long, flowing white beard, which in the film is given to the steadfast major-domo, Jules. Dreyer also reduced the painter’s age considerably: Christensen was a sprightly 45. Dreyer also plays on the character’s sometimes endearing, sometimes unsettling – but always thematically resonant – flaws.

![Image]()

Take Zoret’s passion, for Michael and sometimes even for his painting, which is riveting. He is at fever pitch from the time his protégé walks out on him until he expires, a sadder but wiser human being. And who hasn’t had whiney periods, when they can relate to Zoret’s self-pitying, “Nobody knows how lonely I am. Nobody has the right to make me even lonelier.” And what can you say about his triumphantly masochistic swan song: a vast triptych of himself, as a pitiful old Job-like figure huddled on the ground, wedged in between the even more enormous paintings of the man who got away and the gal who got him? Haven’t you ever felt like that? Yet admirably, the self-possessed Zoret never loses his dignity; and he overcomes his artistic block, brought on by being unable to paint Zamikoff’s eyes, to complete his most acclaimed works.

There’s also something strangely comforting about Zoret’s highly-lauded paintings: not to sound snooty, but they’re kitsch. Zoret’s massive pictures may literally tower over their spectators, but they are basically just academic recyclings of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Michelangelo or, more precisely, Poussin (who might have successfully sued Zoret over “The Victor”). I must confess that I was relieved to hear Casper Tybjerg say on his commentary (which I first listened to only after completing a draft of this review) that many admirers of Michael also consider Zoret’s work derivative, it’s hollow nature an intentional part of Dreyer’s thematic complexity: I could not agree more. If Zoret were noble through and through, and if he were in fact a genius of painting (although it must be hard to find a certified Great Artist who will create masterpieces on demand for a filmmaker, even Dreyer), he would be too removed from common experience to let many people connect with him. He is, to the betterment of the film, flawed, human, real – and that makes him much more interesting than a plaster saint. And his “ordinariness” also makes his ultimate revelation, at the end of the film, all the more powerful, in part because it implies that any of us – and not just a Great Artist – can reach genuine new insight (hopefully without having to die a few minutes later like Zoret).

Now let’s look at some specifically gay aspects of Zoret, and how ultimately (some would say paradoxically) they allow this character to open up the entire film to perhaps universal meaning. The academic-style posturing, the sheer phoniness, of Zoret’s work reminds us – and at the end, perhaps him too – that there is no substitute for life. (It also serves as a sly satire on the throngs of beautifully-attired guests at Zoret’s exhibit, who seem enthralled by his work, repeatedly raising their champagne glasses en masse and toasting The Master.)

![Image]()

It is not Zoret’s art but his life, specifically as a gay man, which inflects the entire film. (And in terms of Dreyer’s body of work, he is a singular master at externalizing the psyche, whether that of an individual, like the title characters in The Passion of Joan of Arc and Gertrud, or an entire culture, as in the Dark Ages in Day of Wrath; or even the darkest recesses of our subconscious in Vampyr: but that phenomenon begins here in Michael.) Sometimes Zoret’s perspective takes a lighter, although still complex form, as with the countess. His jealousy is revealed by how he, and hence the film, sees her as a uniquely visual figure, almost a work of art, albeit in camp terms. She is presented as an enchanting seductress who is feathery (a motif, noted above, which runs throughout the film in many forms), frilly, slinky, almost a parody of a femme fatale. Yet just how “femme” is the countess? When you compare her to her structural counterpart, the sweetly demure Alice, Zamikoff even comes across as boyish: her slender physique is also a far cry from that curvaceous, headless, nude female statue which Dreyer highlights in the first scene. (These comments are about how Zoret, through Dreyer, interprets the character, and imply no disrespect for Nora Gregor, who in 1939 went on to play the aristocratic, and adulterous, Christine de la Cheyniest in Jean Renoir’s tragicomic masterpiece, The Rules of the Game.) In the final scene, she has not only won, and bilked, Michael, but turned him into something demonstrably her own.

![Image]()

For the first time we see him dressed in her style, in silkily ornate chinoiserie, far from his earlier manly state both in suits or, as a work of art in the painting, almost nude. The last thing we see is her cradling Michael in her arms, after learning about his beloved Zoret’s death – but even with her beatific smile it seems to be more of a vamp(ire)’s embrace, which we suspect will end when Michael’s inheritance does, rather than one of true connection and comfort. Or is it? Of course a real-world equivalent of Countess Zamikoff would have psychological complexity instead of the thematic ambiguity of this fictional character, who is simultaneously seductive yet reticent, a home-wrecker yet seeming nurturer. But Dreyer is presenting her, and Michael, not as “real” people but as manifestations of Zoret’s subjectivity: it is up to each of us in the audience to understand the difference.

We must also realize that Zoret’s perspective stems fundamentally from his being a gay man. But what does that mean for this film? Casper Tybjerg’s commentary gives us much to think about when he quotes an historian of gay literature who believes that Bang’s novel – and we can extend this insight to Dreyer’s film – is, paradoxically, a “most pronounced work about homosexuality precisely because it does not speak of it.” In other words, Michael establishes a series of paired seeming opposites about homosexuality – absence and presence, ignoring and knowing, denial and desire – which highlight the proverbial elephant in the room which no one will even mention: conspicuous by its absence.

But Dreyer turns the entire film, on every level, into an expression of Zoret’s gay nature, as it had to be lived in that oppressive time in which “don’t ask, don’t tell” encompassed every level of society. For instance, consider Zoret’s profession: he is a painter. Even beyond the long tradition of GLBT artists, there is the nature of his craft. Zoret is focused on beautiful, albeit kitschy and derivative, surfaces in his work, even as he is drawn to Michael perhaps because of the young man’s visual appeal. By contrast, Switt is no male model but he genuinely cares about and loves The Master, significantly staying with him even after the pretty boy has robbed him blind – even of his most cherished possession, “The Victor,” in which Zoret has valorized his love for the Greek-god-like kid (Michael saw only a quick buck, to appease the countess). Who does Zoret pine over? And who would you pine over – after imagining the characters in whatever gender configuration is most appropriate for you? Again, Dreyer is showing us Zoret’s flawed but understandable humanity. He’s gay, but no better or worse than the straight characters.

This brings us to Zoret’s pervasive influence on the dramatic structure of the film. As noted above, Michael presents a then-unheard of equivalency of same-sex and opposite-sex romantic troubles. But on a deeper level, we can see the relationship between the narrative form and Zoret’s fatalism. Note that he is utterly distraught over Michael’s infidelity but not surprised, just as he accepted Switt’s announcement, in the first scene, that Michael was again “eyeing ballerinas:” Zoret melancholily knows the score. And that deterministic perspective is mirrored in the picture’s tightly-closed form. As mentioned above, the first scene lays out every major character and theme, all of which have been fulfilled – whether tragically, pathetically or both – by the final fade-out: and heterosexuality has, unprecedentedly, not “won.” The all-straight lovers of the subplot have meet their doom (Dreyer even ironically includes the hoary bit about a Monthieu family curse, which further highlights the idea of predetermination), and the heterosexual renewal of Michael is tantamount to his degeneration (if that’s not from Zoret’s perspective, what is). To borrow a metaphor from Zoret’s profession, everything has been tightly framed. Like the ornate frames of his paintings, bounding the action within, so too the entire narrative structure. And if you want to extend the analogy even further, so too the very carefully-guarded, carefully-framed lives of gay people, forced to hide in plain sight.

![Image]()

Further, we can see the distinct perspective of this gay artist Zoret in Dreyer’s patented visual framing techniques, which are simultaneously fabulous and unsettling. All of those devices – including the use of iris shots and the moving spotlight – revolve around Dreyer’s pioneering use of the close-up to expose psychological complexity; but the close-ups, and their related effects, are also notable for their self-consciousness. This is especially apparent when Dreyer uses close-ups at their most abstract, as when he combines his iris technique with extreme mid-ground lighting (the background and foreground are pitch dark, while the character’s face is caught in a scalding beam of light). The entire person is then condensed into just their face, and that in turn is suspended in blackness. That technique not only forces us to concentrate intensely on the revelations about their character as expressed in their face, and especially eyes, it also provides an abstract visual frame.

If we are to relate this to Zoret’s perspective, it can be said to work on a spiritual level, with these characters in a kind of limbo, perhaps even bringing to mind the long artistic tradition of scenes of hell, as in depictions of Dante’s Inferno or even Christensen’s recent film Häxan. Although I do not want to cheapen Dreyer’s achievement by literalizing his visual metaphor, you could draw a parallel between the lack of self-knowledge of Zoret, as well as all of the other principal characters, and this visual representation. Dreyer, and by extension Zoret, have literally disassociated their heads from their bodies (a strange complement to that memorable statue of the female nude, which consists only of her body) and then further disassociated them from the world around them, as they hover – often with their heads motionless, even as their expressions register subtle but important shifts – in an amorphous black space. Dreyer the cinematic artist has combined space, lighting, composition, psychology, and even the hint of a spiritual dimension, into unique ambiguous beauty. But if you like, you could also extrapolate this technique to the psychology of Zoret as a gay man. Of social necessity, he must remain highly self-conscious (so that he never slips and reveals his true nature) and carefully “framed,” and as a result his head (reason) is disconnected from his body (passion), even as he feels cut off from the world and surrounded by darkness. Yet, paradoxically, Dreyer is able to transcend Zoret’s subjectivity, making the “artistic effect” of those unique close-ups ravishingly beautiful, if a bit unnerving, in their own right, and genuinely revealing of the character’s emotional depths.

![Image]()

The element which ties together all of these elements – dramatic, visual, psychological – is stasis, towards which the entire film inexorably moves. Note the finality of the dramatic form, in which everything raised in the opening is resolved by the final scene (although the relationship of Michael and the countess seems “open” at picture’s end, we all know what will become of it). Zoret as an artist turns living people into static representations painted on canvas. We have just looked at Dreyer’s use of close-ups, including the noticeable and unsettling stillness with which he captures the character, often unmoving and isolated in a narrow shaft of light against a dark background and foreground. The most obvious example of stasis is, of course, the climactic death of Zoret. But Dreyer extends its significance far beyond a mere plot point, even as he ultimately moves the film’s perspective beyond that of the gay Zoret, as we have been looking at, and into something universal.

On the level of craft, Dreyer and Christensen do the seemingly impossible: they actually make me believe that a man can die of a broken heart. (How many hundreds of movies have tried and failed at this, stretching from the first days of film to last night’s sudsy TV opus.) More extraordinary than that is Dreyer’s radical sympathy for the gay protagonist. Of course, death (either suicide or murder: take your pick) was the fate of almost all gay and lesbian characters, in fiction and film, until just the last quarter century. But here Dreyer focuses on the purely emotional nature of Zoret’s demise: he doesn’t take poison or turn on the gas jets with the windows closed. He loved, as Shakespeare once put it, not wisely but too well. He not only remained true to his passion, which he was able to channel into his painting (which at least the dozens of tony people at his reception enjoyed), but to himself.

The film’s most memorable, and ambiguous, line also serves as the most conspicuous way for Dreyer, and Zoret, to keep the structure closed. The first thing we see, on an intertitle card, is the same as the artist’s dying words (again connecting him with the overall form): “Now I can die in peace, for I have seen true love.”

With the epiphany implied by that line, I believe that Dreyer actually opens up the film – for the first time, on any level – beyond its previously, and relentlessly, closed nature.

![Image]()

But what does Zoret’s phrase mean? People have posited many different interpretations. Perhaps the most far-out opines that Zoret must be referring to his ever-faithful elderly majordomo! The most popular interpretation among those people who refuse to even consider the possibility of homosexuality (incredible as that may sound) in the film is the “normal” heterosexual couple of Michael and Zamikoff: but, as I noted above, their days together seem numbered in direct proportion to his income. Certainly Switt, as redefined by Dreyer in this film (recall how very different he is from Bang’s original), is a contender, as he lovingly stays with the artist, then even swallows his disgust as he goes to fetch the unfaithful object of Zoret’s desire. Still, I feel that the “true love” Zoret refers to is actually within himself – not in some narrow solipsistic way but in a much larger sense. Of course, each of us must decide for ourself how to read the line and apply it to the film, and certainly some of your interpretations will be quite different from mine – but onwards!

The line is, of course, both poignant yet genuinely hopeful both for Zoret and, especially, us (because we’re not going to die until our individual final reel comes up). Now that Zoret and the film have reached their final point of stasis, the artist seems to understand what is real: his love for Michael, certainly, but beyond that there is something more. He comes to realize that his love for Michael was ultimately a path to his own self-enlightenment. He sees that his love is internal, although it was directed towards another. If this is indeed what Dreyer is saying, it is a profoundly humanistic view. With a huge cross looming above his deathbed, you might expect Zoret to experience a last-second conversion to conventional faith, like, say, Oscar Wilde (who was convinced to convert to Catholicism a few hours before he expired). But Zoret remains inner directed.

The feeling which Zoret seems to find inside himself is both real and humanely redemptive; extraordinarily for the time, it is achieved without the aid of religion (which would likely have seen only his “sodomitical” nature and hence condemned him to a fate even worse than the film’s visual limbo effect). And let’s not forget the historical context: at this same time Germany’s Paragraph 175 and similar laws throughout the world, were sending men like Zoret to prison. Yet here the spiritual figure, whom we are supposed to identify with, was at the time a criminal (some people might possibly see a parallel with an earlier outsider and “criminal”: as an artist and liberal Christian, Dreyer’s lifelong but unfulfilled ambition was to film Jesus; at least his detailed screenplay has been published.) On one level Dreyer – always of a champion of the rights of religious minorities (Love One Another), women (Gertrud) and all oppressed people – has allowed us to stretch our imaginative and moral faculties – whatever our personal natures – to see a gay man not only as human, but as someone who has, at least by implication, found ultimate love. Zoret’s art was strictly for show, but Dreyer’s is beautiful, ethical and spiritual. Until its final moments, this flm has been marked by its relentless closed nature, in form, imagery and themes. But now, the implications of Zoret’s revelation have burst it open, giving him and us hope. Not in a sectarian sense, but in a definingly humanistic way, letting us see the connections between these benighted characters, our own humanity, and the transcendent power of art and love.

![Image]()

I believe that Dreyer is not only a cinematic genius but one of the world’s great artists. This film, like his later triumphs, is both clear, even with its purposeful ambiguities, and very deep. The more closely you look, the more you can see and intuit, whether it’s the witty play of decor against relationships, form exposing character (abstracted faces suspended in frames, both literal and metaphorical), or the unexpected emotional and spiritual epiphany of a man we might have written off as a masochistic old fool, yet who in the end radically opens the film in ways both unexpected and profound.

Dreyer’s unique combination of psychology, drama, image, and rhythm creates an interplay of aesthetic distance and emotional intimacy which some people may find unsettling (or worse, “boring”), while others of us are riveted by the fullness and intensity of the experience. If you connect with Dreyer, his masterpieces, beginning with Michael, can seem an expressive summit of artistic and spiritual life, of humanity itself.

![top top]()

Crew

- Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer

- Written by Dreyer & Thea von Harbou,

- Based on the Novel by Herman Bang

- Produced by Erich Pommer

- Cinematography by Karl Freund & Rudolph Maté

- Production Design by Hugo Häring

|

Cast

- Benjamin Christensen as Claude Zoret

- Walter Slezak as Michael

- Nora Gregor as Countess Lucia Zamikoff

- Max Auzinger as Jules, the majordomo

- Robert Garrison as Switt

- Dider Aslan as Duc de Monthieu

- Alexander Murski as Adelsskjold

- Grete Mosheim as Alice Adelsskjold

- Wilhelmine Sandrock as Widow de Monthieu

- Karl Freund as Leblanc, the art dealer

|

http://jclarkmedia.com/film/filmreviewmichael.html

Una nave sta per salpare. Un ragazzo e una ragazza non vogliono assolutamente perderla. Salgono in moto, trafelati. Il porto è lontano e il tempo stringe. Accelerano, ormai a rotta di collo. C’è però una macchina che non li lascia passare. Ormai siamo tutti con loro, odiamo ogni ostacolo. Forza, fatti da parte, abbiamo fretta. E al momento del sorpasso, l’autista dell’auto, il nemico che frena la nostra corsa e i nostri desideri, svela il suo volto… La Morte. Stacco. La passerella viene ritirata, il traghetto è in partenza. Ma più in basso, a pelo dell’acqua, si intravede un’altra barca più piccola. Ai remi c’è una figura nera, i passeggeri sono due bare. Anche nella più triviale delle Pubblicità Progresso (una campagna per la prevenzione degli incidenti stradali), Dreyer incontra il peccato e la sua punizione.

Dante albanesi

https://baikcinema.wordpress.com/2008/03/07/raggiunsero-il-traghetto-di-carl-theodor-dreyer/

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Die Gezeichneten (1922) – Gli stigmatizzati

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2013/06/01/carl-theodor-dreyer%E2%80%99s-die-gezeichneten-1922-gli-stigmatizzati/

Il cinema di Dreyere la spiritualità del Nord Europa.Giovanna d’Arco, Dies irae, Ordet

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2012/02/13/il-cinema-di-dreyere-la-spiritualita-del-nord-europa-giovanna-darco-dies-irae-ordet/

To see Michael in a historical context, here are brief remarks on

To see Michael in a historical context, here are brief remarks on

UN LETTO FRA LE LENTICCHIE

UN LETTO FRA LE LENTICCHIE